George Northup

Legacy in Fine Art Bronze Sculpture

Sporting Art Wildlife Art

Northup Fine Art

While painting is the story of play between color and light.

Sculpture is the story of play between movement and form.

Each the story of art and the stretch to express the otherwise inexpressible

-George Northup

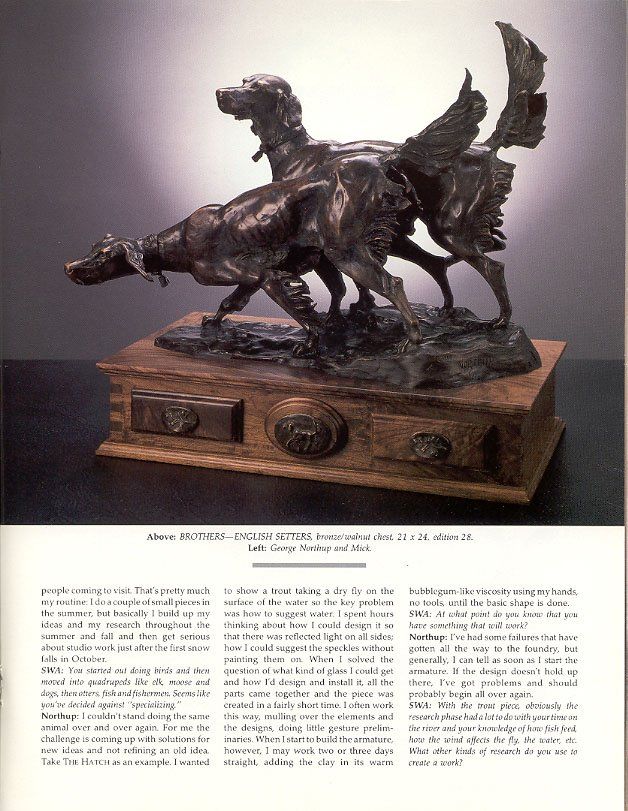

George Northup Bronze Sculptures

-

Leaving Early

Bronze Quail Lamp

-

King Of The Hill

Mule Deer Bronze Sculpture

-

Incoming

Labrador Bronze Bookend

-

Bronze Aspen Floor Lamps

59" & 62"

-

Beaverhead Browns

Bronze Trout Lamp

-

Cruising Trout

Bronze Bookend

7" x 12" -

Doe Ray Me

Mule Deer Bronze Lamp

-

Nymphing Trout

Bronze Bookend

7" x 12" -

God's River Brook Trout

Bronze Lamp

28"h x 22"w -

Green Drake Day

Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout

27" x 27" x 9"

*One Remaining* -

Labrador Look

Bronze Labrador Lamp

*Sold Out* Special Legacy Edition release -

Marking Those Words

Bronze Fox Sculpture Bookend

-

Ringneck

"Bronze Pheasant Lamp"

-

Undivided Attention

Bronze Whitetail Deer Sculpture34" x 33"

-

Noontime Covey

Bronze Quail Lamp

-

Elephant Bookend

Elephant Fine Art Bronze Bookend 8" x 14"

-

"Evade & Escape"

Mule Deer Bronze Lamp

35" x 26" x 15" -

Elephant Walk

Bronze Elephant Sculpture

-

Milo

Bronze Cat Sculpture

-

Caddis Hatch

Bronze Trout Lamp with Copper Shade

29"h x 14"w x 9"d -

At Heel

Bronze Labrador Bookend

-

Dark Waters

Bronze Loon Lamp

-

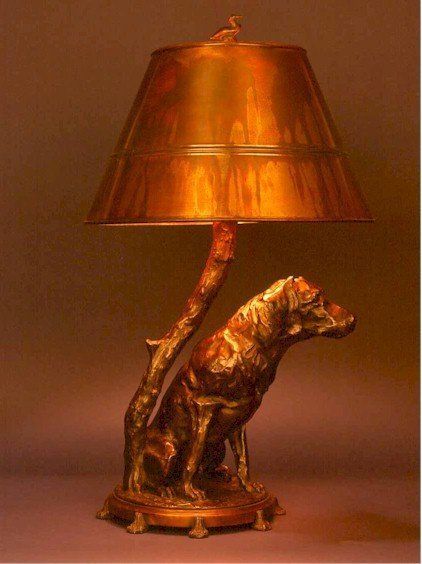

Hard Point

Bronze Sculpture lamp of an english setter on point

-

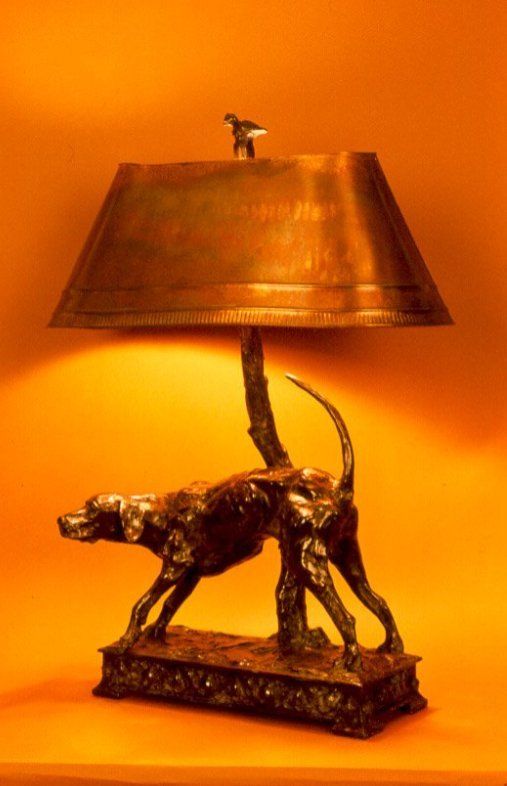

Southern Style I

English Pointer Lamp

-

Southern Style I

English Pointer Lamp

-

Southern Style II

English Pointer Lamp

Legacy Closed Edition Release

For the duration of his career, George has reserved the most valuable numbers in each sculpture edition. For a limited time, he will be releasing his numbers One, Two and Three of select closed edition sculptures. This remarkable opportunity to acquire the last of his most beloved and collected sculptures will not be available through galleries. Each piece will be released with notice only given to collectors and those on

Visit Legacy Edition Offerings

George Northup & Clint Orms

Two American masters converge to create a legendary, limited offering.

Visit the Northup - Orms Collection

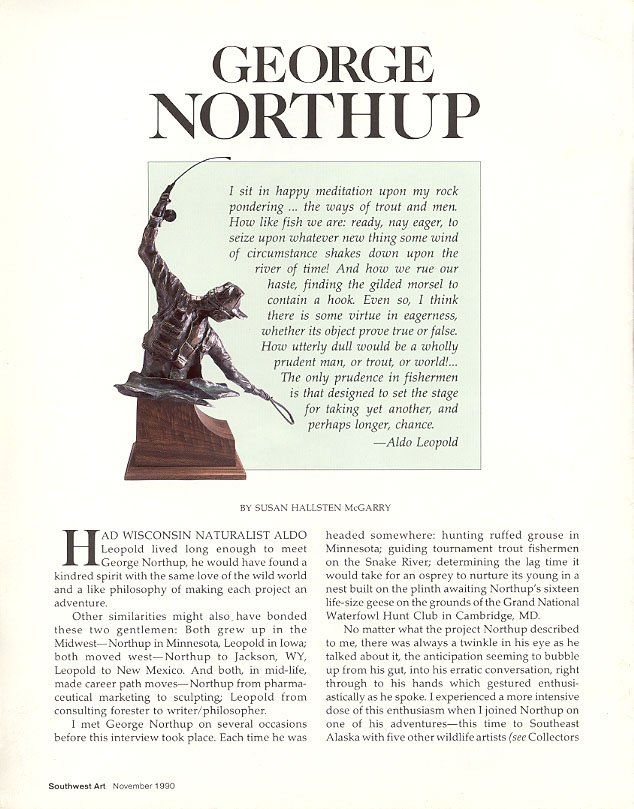

I sit in happy meditation upon my rock pondering ... the ways of trout and men. How like fish we are: ready, nay eager, to seize upon whatever new thing some wind of circumstance shakes down upon the river of time! And how we rue our haste, finding the gilded morsel to contain a hook Even so, I think there is some virtue in eagerness, whether its object prove true or false. How utterly dull would be a wholly prudent man, or trout, or world!... The only prudence in fishermen is that designed to set the stage for taking yet another, and perhaps longer, chance.

—Aldo Leopold

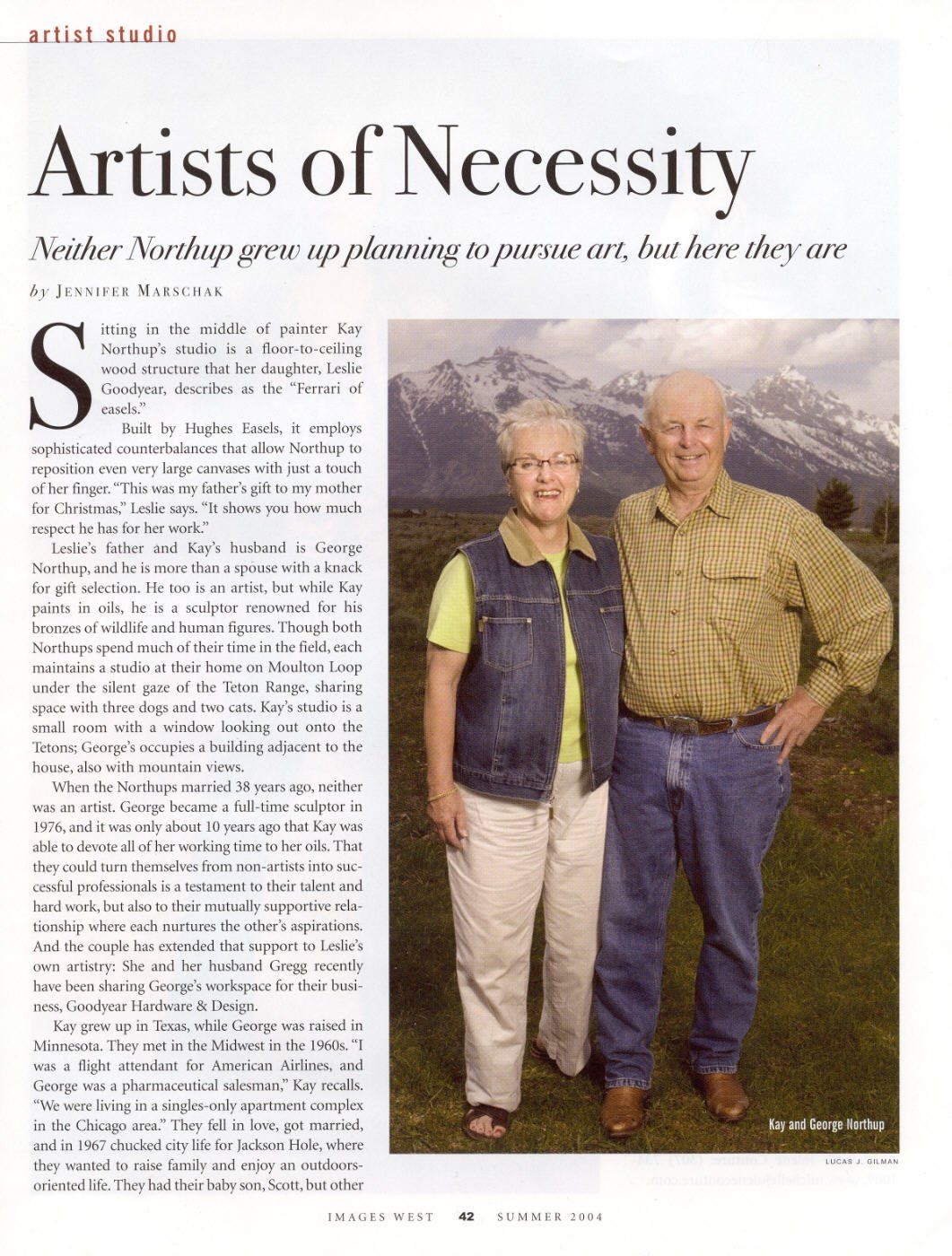

HAD WISCONSIN NATURALIST ALDO Leopold lived long enough to meet Bronze Sculptor George Northup, he would have found a kindred spirit with the same love of the wild world and a like philosophy of making each project an adventure.

Other similarities might also have bonded these two gentlemen: Both grew up in the Midwest—Northup in Minnesota Leopold in Iowa; both moved west—Northup to Jackson, WY, Leopold to New Mexico. And both in mid-life, made career path moves— Northup from pharmaceutical marketing to sculpting; Leopold from consulting forester to writer/philosopher.

I met George Northup on several occasions before this interview took place. Each time he was headed somewhere: hunting ruffed grouse in Minnesota; guiding tournament trout fishermen on the Snake River; determining the lag time it would take for an osprey to nurture its young in a nest built on the plinth awaiting Northup's sixteen life-size geese on the grounds of the Grand National Waterfowl Hunt Club in Cambridge, MD.

No matter what the project Northup described to me, there was always a twinkle in his eye as he talked about it the anticipation seeming to bubble up from his gut, into his erratic conversation, right through to his hands which gestured enthusiastically as he spoke. I experienced a more intensive dose of this enthusiasm when I joined Northup on one of his adventures—this time to Southeast Alaska with five other wildlife artists. There learned more about his obsession with fly fishing. Later, when this September 1989 conversation took place. I uncovered how the one-on-one process of fishing or bird hunting goes hand in glove with the creation and marketing of George Northup's fine art.

Seated on a couch looking at the Grand Tetons and Mount Moran through floor-to-ceiling windows the artist periodically shooed away “Mick,” his six-year-old black Lab who plopped its square muzzle and solid frame at our feet. In front of us was a handsome double-sided fireplace made of over 31 tons of stone queened and built by Northup and wife Kay back in 1975 when their three children were still adolescents and when Jackson Hole boasted only a handful of resident artists and even fewer galleries.

INT: You come out to Jackson without a job and without two haying seen the place. What made you act on such a long shot?

Northup: Kay and I were looking for a good place to raise kids, and we knew about the developing ski industry in Jackson. I'd always been an outdoorsman—hunting and fishing and skiing—so Jackson seemed like a perfect place for me. It was a little harder on Kay, who was more of a city girl, but she adjusted quickly.

INT: You weren't doing art at this time?

Northup: Right. I had no idea what I was going to do. We moved onto the Snake River Ranch, the biggest in the valley, where we met real cowboys and teamed about the cattle industry. I had various jobs as a plumber, bar and restaurant manager, building contractor, carpenter, fishing and hunting outfitter, ski instructor, cook, white-water raft trip organizer… in Jackson you have to be able to do just about everything since so much of the economy revolves around the changing seasons. Wildlife art and Sporting art were a long way from my radar

INT: Have you studied art?

Northup: I have never had any formal art training but as a kid growing up in Detroit Lakes, MN, I had a chance to see quite a bit of good art. My uncle, Waller Swanson, is a super western painter (he’s over 80 now and were still close) and my two aunts taught art in college. They insisted that I and my three sisters attend all the important an exhibits in Minneapolis, St. Paul or wherever, and encouraged us to pick out our favorite pieces.

When we got to Jackson, Kay and I spent our spare time looking in the galleries, particularly Trailside, where I got to know the owner at the time, Ginger Renner. Ginger used my service, as an outfitter when artists or clients came to town. I would entertain them with gourmet dinners on the river and then listen to their conversations as the sun went behind the mountains. It was on one of these trips that I first met John Clymer (WA 1907-1989 WY) who became both a mentor and close friend.

INT: So that combined with your love of wildlife…

Northup: Yes. Id built up a pretty good working knowledge of birds, fish and mammals while in Minnesota, so in Jackson I was very comfortable answering questions even from biologist, about the wildlife here. I really enjoyed meeting artists like Harry Jackson and seeing his incredible bronze sculptures. I was curious about how they were made, and when a friend, Joe Shellenberger, started teaching a class in fine an casting for the local art association I offered to be his assistant, since I couldn't afford the tuition. That's where I created my first bronze sculpture.

INT: And you were hooked?

Northup: Not exactly. I didn't have this craving to be an “artist,” but the winters are long here in Jackson and the challenge of doing something creative during those months is compelling.

INT: When was this?

Northup: Let's see. 1970. I think because it was 1971 that I made my second piece. It came about following a white-water raft trip. I had thirteen kids on my raft when I broke an oar, lost control and tipped everyone into the water. I didn't have a life jacket on and got caught in what we call a “hydraulic” where churning water pulled me down to the bottom of the river. Hypothermia was beginning to set in when I came up for the third time and a sixteen-year-old girl named Melody who was wearing a life jacket grabbed hold of me and we swam to shore.

For a long while I couldn't quit thinking about this experience. A friend brought over some clay and told me to start a sculpture. It became a grouping of teal and when Christine Mollring at Trailside Gallery saw it, she told me she thought she could sell it. A man from Minneapolis bought the first one, my first fine art collector, which gave me enough money to cast a second one. That's when I got hooked and had to find a second job for Kay.

INT: So when you got a loan for your house in 1975, you put “artist” on the occupation line?

Northup: Right. We decided to build under the Tetons so that we could enjoy Poverty with a view. But I don't know whether I'll ever truly consider myself an artist since I have no formal training. I'm still learning by working directly with great artists such as Ken Bunn, George Carlson, Veryl Goodnight, Ned Jacob, Bill Reese, Hollis Williford, Bob Kuhn, etc. I've placed many a two-hour long-distance phone calling for help, and I've organized a number of workshops here in Jackson, bringing in these great sculptors and painters whom I get to have in my back yard. Artists like Bill Reese and Bob Kuhn have become close friends—we go fishing together and talk and I learn.

INT: I've wondered how you balance out all these extracurricular activities with your art.

Northup: Early on John Clymer sat me down and told me to divide my year into summer and winter and not to bother doing anything major in the summer when there are so many distractions and people coming to visit- That's pretty much my routine: I do a couple of small pieces in the summer, a trout sculpture or sporting art piece, but basically I build up my Ideas and my research throughout the summer and fall and then get serious about studio work dust after the first snow falls in October.

INT: You starred out doing birds and then moved into quadrupeds like elk moose and dogs. Then otters, fish and fishermen. Seems like you've decided against "specializing."

Northup: I couldn't stand doing the same animal over and over again. For me the challenge is coming up with solutions for new ideas and not refining an old idea. TAKE THE HATCH as an example. A cross medium trout sculpture. I wanted to show a trout taking a dry fly on the surface of the water so the key problem was how to suggest water. I spent hours thinking about how I could design it so that there was reflected light on all sides; how I could suggest the speckles without painting them on When I solved the question of what kind of glass I could get and how I'd design and install it, all the parts came together and the piece was created in a fairly short time. I often work this way, mulling over the elements and the designs, doing little gesture preliminaries. When I start to build the armature, however, I may work two or three days straight, adding the day in its warm bubblegum like viscosity using my hands no tools until the basic shape is done.

INT: At what point do you know that you have something that will work?

Northup: I've had some failures that have gotten all the way to the foundry, but generally, I can tell as soon as I start the armature. If the design doesn't hold up there, I've got problems and should probably begin all over again.

INT: With the trout piece obviously the research phase had a lot to do with your time on the river and your knowledge of how fish feed how the wind affects the fly, the water, etc. What other kinds of research do you use to create a work?

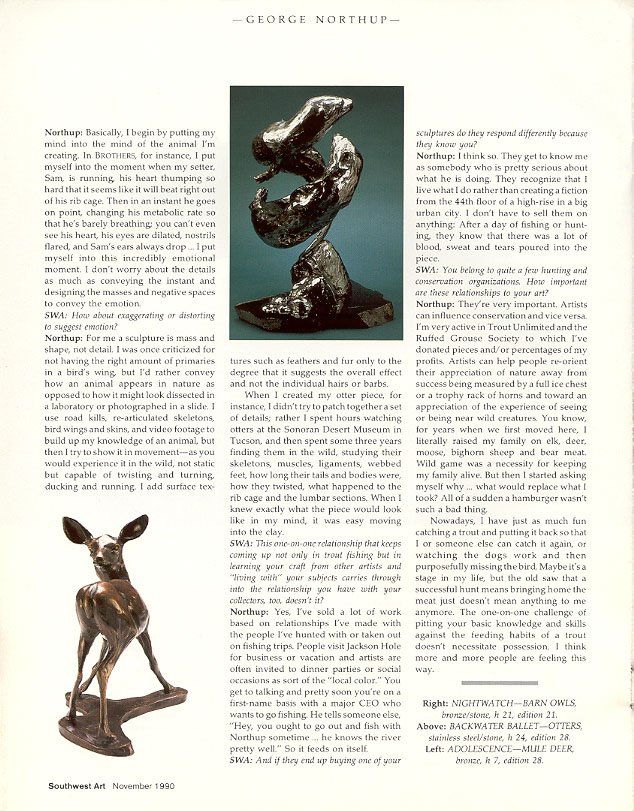

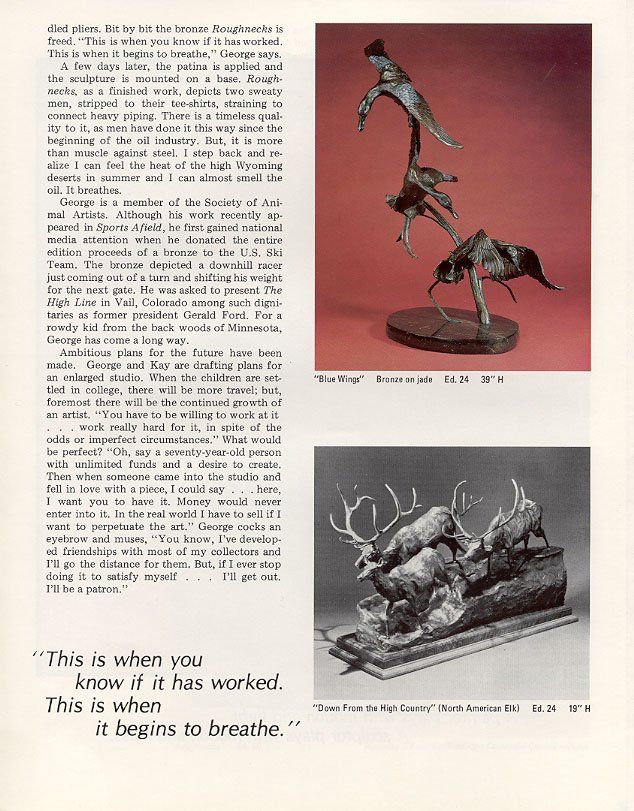

Northup: Basically, I begin by putting my mind into the mind of the animal I'm creating. In BROTHERS, for instance, a sporting dog sculpture, I put myself into the moment when my setter, Sam, is running, his heart thumping so hard that it seems like it will beat right out of his rib cage. Then in an instant he goes on point, changing his metabolic rate so that he's barely breathing you can't even see his heart, his eyes are dilated, nostrils flared, and Sam's ears always drop... I put myself into this incredibly emotional moment. I don't worry about the details as much as conveying the instant and designing the masses and negative spaces to convey the emotion.

INT: How about exaggerating or distorting to suggest emotion?

Northup: For me a sculpture is mass and shape, not detail. I was once criticized for not having the right amount of primaries in a bird's wing, but I'd rather convey how an animal appears in nature as opposed to how it might look dissected in a laboratory or photographed in a slide. I use road kills, re-articulated skeletons, bird wings and skins, and video footage to build up my knowledge of an animal, but then I try to show it in movement—as you would experience it in the wild, not stalk but capable of twisting and turning ducking and running. I add surface textures such as feathers and fur only to the degree that it suggests the overall effect and not the individual hairs or barbs.

When I created my otter piece. for instance, I didn't try to patch together a set of details; rather I spent hours watching otters at the Sonoran Desert Museum in Tucson, and then spent some three years finding them in the wild, studying their skeletons, muscles, ligaments, webbed feet, how long their tails and bodies were, how they twisted, what happened to the rib cage and the lumbar sections When I knew exactly what the piece would look like in my mind, it was easy moving into the clay.

INT: This one-on-one relationship that keeps coming up not only in trout fishing but in learning your craft from other artists and “living with” your subjects carries though into the relationship you have with your collectors too, doesn't it?

Northup: Yes, I've sold a lot of work based on relationships I've made with the people I've hunted with or taken out on fishing trips. People visit Jackson Hole for business or vacation and artists are often invited to dinner parties or social occasions as sort of the “local color.” You get to talking and pretty soon you're on a first-name basis with a major CEO who wants to go fishing. He tells someone else. “Hey, you ought to go out and fish with Northup sometime… he knows the river pretty well.” So it feeds on itself.

These conversations are how many of my best corporate art and corporate gift relationships started.

INT: And it they end up buying one of your sculptures do they respond differently because they know you?

Northup: I think so. They get to know me as somebody who is pretty serious about what he is doing. They recognize that I live what I do rather than creating a fiction from the 44th floor of a high-rise in a big urban city. I don't have to sell them on anything: After a day of fishing or hunting, they know that there was a lot of blood, sweat and tears poured into the piece.

INT: You belong to quite a few hunting and conservation organizations. How important are these relationships to your art?

Northup: They're very important. Artists can influence conservation and vice versa. I'm very active in Trout Unlimited and the Ruffed Grouse Society to which I've donated pieces and/or percentages of my profits. Artists can help people reorient their appreciation of nature away from success being measured by a full ice chest or a trophy rack of horns and toward an appreciation of the experience of seeing or being near wild creatures. You know, for years when we first moved here, I literally raised my family on elk, deer, moose, bighorn sheep and bear meat. Wild game was a necessity for keeping my family alive. But then I started asking myself why... what would replace what I took? All Ma sudden a hamburger wasn't such a bad thing. Nowadays, I have just as much fun catching a trout and putting it back so that I or someone else can catch it again, or watching the dogs work and then purposefully missing the bird. Maybe it's a stage in my life, but the old saw that a successful hunt means bringing home the meat just doesn't mean anything to me anymore. The one-on-one challenge of pitting your basic knowledge and skills against the feeding habits of a trout doesn't necessitate possession. I think more and more people are feeling this way.

INT: You are optimistic about the future in terms of our consciousness in saving wild lands and creatures?

Northup: I'm cautiously optimistic. People often say here in Jackson. “Well, you should have fished here 40 years ago, or 20, or 10 years ago.” The problem is that one generation doesn't remember what the earlier generation remembers, so we are content with less and less. Still, the public—taxpayers—are making demands about saving things, about cleaning things up. The Alaskan Valdez oil spill is a good example: The people of Alaska didn't say,

“Please clean this up.” They insisted, “Hey, we’re not satisfied with the cleanup, you're not done yet” Exxon was forced to listen. That would have been unheard of ten years ago.

INT: What's your personal goal in this?

Northup: To leave the world a little bit better than it was when I got here. When you see a dead salmon, its giant, gold eye staring at you, knowing all these fish could be gone, it's an emotional jolt, a reminder that it's all going to end and we had better do something about it now.

INT: And with your art?

Northup: I read a quote that Bob Kuhn made many years back that went sumo thing like, “You’ll never be remembered for the things you've done like somebody else but for the independence and creativeness of your thinking.” Art for me means Meeting new challenges so that I'm constantly growing. The excitement comes in solving a problem that has never been solved. A turtle has to stick its neck out before it can walk: I'm putting my creativity and independence on the line every time I sign my name to a piece.